When it comes to mindless journalistic blunders, there are brain cramps and then there are lobotomies.

Example of a brain cramp: the time in the late-1990s when, as a newspaper reporter, I referred to a high school student as “Dustin Hoffman.” He shared a first name with the famous actor, but not the last name, and my mind drifted into auto-celebrity actor mode as I tapped out my story.

The teen’s last name? I don’t remember, but I do recall his parents being peeved that I had interviewed the 17-year-old without their consent. (The story was about a teacher who had been accused of sexually assaulting another student during an overseas trip.)

To make my mistaken-attribution saga even stranger, those same parents’ upset was assuaged by what they saw as my intentional decision to shield his identity by concocting a false (and famous) last name. Apparently, they thought I was exercising some journalistic ethic in doing so. Nope, it was just a mindless blunder, of the brain-cramp variety.

Which brings me to that other type of journalistic blunder: the lobotomy.

A literal lobotomy, for those who are not familiar, is a brutal, discredited form of psychosurgery, “a neurosurgical treatment of a mental disorder that involves severing connections in the brain’s prefrontal cortex.” In layman’s terms, patients may be relieved of mental disorders, but there is a great risk that they will be left as docile, almost-vegetative souls.

A figurative lobotomy played out just last night, through a dialogue between MSNBC’s Brian Williams and Mara Gay, a New York Times editorial board member. The two astonishingly, staggeringly, mind-blowingly treated as truth a Twitter post that mangled math beyond measure—or, at least, by a roughly 650,000-to-1 ratio.

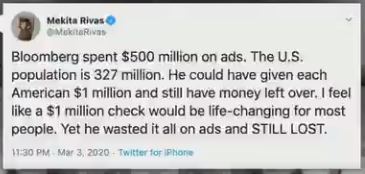

Here was the Tweet by freelance journalist Mekita Rivas:

In response, Williams declared, ““When I read it tonight on social media, it kind of all became clear…It’s an incredible way of putting it.”

Incredible, indeed–as in “not to be believed.” His use of the word didn’t raise any red flags, however, as Gay echoed the word and chimed in: “It’s an incredible way of putting it. It’s true. It’s disturbing. It does suggest what we’re talking about here: there is too much money in politics.”

To quote the first words of New York Post’s Steven Nelson’s account of the debacle: They’re a couple of on-the-airheads!

My bit of cleverness: MSNBC could stand for May Share Numbers Before Consideration.

The blame goes beyond Williams and Gay. It was not only their slip-up, but that of the entire crew, including producers and graphic design team. None of ’em recognized the abject absurdity of the tweet. (The actual amount would be about $1.53, or $999,998.47 less than was stated.)

As you may suspect, it wasn’t long before the cascade of corrections in the Twittersphere set the network straight and the instigator of the math mess deleted it, then updated her profile to state “I know, I’m bad at math.” Later, Williams’ show released this statement:

“Tonight on the air we quoted a tweet that relied on bad math. We corrected the error after the next commercial break and have removed it from later editions of tonight’s program. We apologize for the error.”

Mistakes happen, including math mistakes. But what was initially an innocent mishap by a single math-challenged individual should not have come anywhere close to being amplified by a major network like MSNBC. Theirs was a blunder of epic proportions, on an alarming level that rightfully would cause anyone to question the network’s judgment, discernment and intelligence on other stories.

The embarrassing episode underscores why there is such a desperate need for improved numeracy, or math literacy, for citizens. And it takes on exponential urgency when it comes to those stewards of story-telling in the journalism realm.

That is why I developed “Go Figure: Making Numbers Count” nearly 20 years ago, with journalists as my primary audience for the first decade thereafter. Traveling throughout the United States to spread the Go Figure Gospel, I have felt a strong sense of public service with every math-challenged reporter, editor or other media professional I have trained. These are often folks who thought they were getting away from math when they got into journalism–only to realize that numbers are inextricably linked with just about any kind of story-telling.

In recent years, I have expanded the program to a diverse array of audiences, including the general public. In fact, around the same time Williams and Gay were fumbling through this epic math gaffe last night, I was at the Itasca Community Library leading a numeracy workshop. With a focus on the 2020 Election cycle, the program was called “Lies & More Lies, How it All Adds Up.”

Among the topics that I covered: the one-to-1,000 ratio between one thousand and one million (1,000 thousands) and the same one-to-1,000 relationship between one million and one billion (1,000 millions). For example—and it is one that I have used for over 20 years in my myriad writings on numeracy—one million seconds is a shade over 11 ½ days and one billion seconds is nearly 32 years.

Fittingly, I referred to the Mike Bloomberg campaign spending in the “Golympics” quiz that is a key feature of my session. Here’s the question:

Michael Bloomberg spent over $500 million in a three-month span before dropping out of the race on March 4th, the day after Super Tuesday. What proportion of his net worth does that amount to?

- 9%

- Less than 1%

- 2.7%

The answer is “b,” or less than 1 percent, because Bloomberg’s net worth is over $50 billion. You may want to look it up to be sure, but trust me, you can take that stat to the bank.

Want to learn more about my numeracy programs, including the Election 2020-themed “Lies, Damn Lies & Navigating the Presidential Campaign Trail” sessions, with over a dozen scheduled in the Chicago area through October? Visit www.GoFigureMakingNumbersCount.com.

Related Posts:

In the wake of NBC’s Brian Williams’ fall from grace, apologists creep out of the woodwork

My percentage / percentage point primer and plea